|

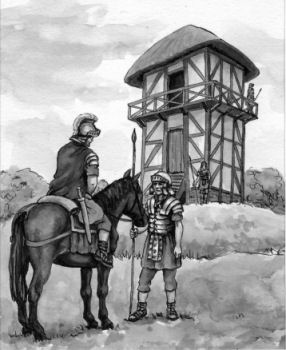

By clicking on the subject of your choice in the sub index below, you will be taken directly to your selected page, which will open in the same window. To view further pages within this section, you can either use the next button at the foot of the page, which will move you through the section one page at a time. You can also return to this index page by using the Previous button, again at the foot of the page, or you can use also make use of your back button. You can of course also open all links from the index page in a separate window using the right click facility on your mouse and selecting "Open Page in New Window". There is also a fifth option of using the Site Index button at the foot of the page to navigate from the main index page. Five methods a all designed to make navigating this site as easy as possible. Following the invasion of AD43, and the battle of Medway, the Second Augustan Legion under the command of Titus Flavius Vespasianus (Vespasian), destined to become Emperor of Rome in AD69, was charged with the task of conquering the Celts of Southern Britain. According to Suetonius, these operations were conducted partly under Claudius, and partly under Vespasian's commander, Aulus Plautius. During the long march westwards, he engaged the enemy thirty times in battle, subdued two tribes, conquered Vectis or the Isle of Wight, and penetrated as far as Dorset where they had to overcome the Durotiges and their Hill Forts. A major and bloody battle seems to have taken place at Maiden Castle (a major Celtic hill fort) and also at Hod Hill, and on occasion the Romans had to lay siege to the hill forts and starve the inhabitants out in order to achieve victory. Having accomplished the conquest of Dorset the Romans then had the task of moving into Somerset and taking on the defended hill forts of the Dumnonii, who would have had some time to enhance their defences, and who also would no doubt have had their resolve hardened by the fate of their neighbours, and who therefore may also have had their numbers boosted by refugees. The end of their long march lay at a small settlement at the head of the Exe Estuary, Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter). This small settlement was soon to grow, and become the legionary headquarters for the whole of the southwest, supplied and supported by the port of Topsham. It is unlikely that it was a popular posting with the Legion being far from Rome and in a somewhat remote region of the province, probably desolate and windswept, important perhaps because of the tin, and there are records of tin being mined on Exmoor during the Roman occupation, but not popular with rich Roman farmers who preferred to build their villas in adjoining Somerset. It is possible that this remoteness and relative unimportance of the area was a contributing factor in the decision, late in the first century AD, to move the legion out of Exeter and eventually onto their new base at Caerleon, known to the Romans as Isca, in South Wales. It may also have been a decision helped by the degree of co-operation they apparently received from the Dumnonii. What little evidence available would certainly appear to suggest that once they accepted that defeat was inevitable, they did little to incur the wrath of the Romans. 1. Exeter, fortress of the Second Augustan Legion and subsequently the capital of the Civitas Dumnoniorum, played an important part in the history of Roman Britain. In about AD67 the legion itself was transferred to a major new base at Isca Silurum (present day Caerleon, near Newport in South Wales) and the Exeter fortress was abandoned. However, shortly after, work began to convert the site into a civilian town, known as Isca Dumnoniorum. Its public buildings included a forum and basilica (town hall), a market place and public baths. In about 180-200, the City Wall was built, enclosing 93 acres, a much larger area than that of the fortress and early town. About two thirds of the City Wall remains; it has been patched and repaired over the centuries, but some of the original Roman masonry can still be seen. The sites of the gates were retained in the following centuries, but very little still remains of the Roman grid street pattern, with only the northern part of High Street following the Roman lines. 2. According to the Greek Geographer and Historian, Strabo (c.63BC - after AD21), trade between Britain and the Roman world boomed during this period with the British exporting: "Grain, cattle, gold, silver and iron, also hides, and slaves, and dogs that are by nature suited to the purposes of the chase." Previous Last Edited 03/07/2006 Copyright © 2000-2006 Witheridge Unless otherwise indicated on the page in question, the photographic images reproduced on this site belong to the Witheridge Archives, and, as such may not be reproduced for commercial purposes without written permission. However, you are welcome to use any of the photographs belonging to the archive for personal and/or non-commercial use. Any material shown as not being owned by the archive may not be reproduced in any form without first receiving written permission from the owner of the material in question. The copyright for the illustration of the Roman Watch Tower belongs to Witheridge Artist and Illustrator Jenny Bidgood. |